Legal Billing

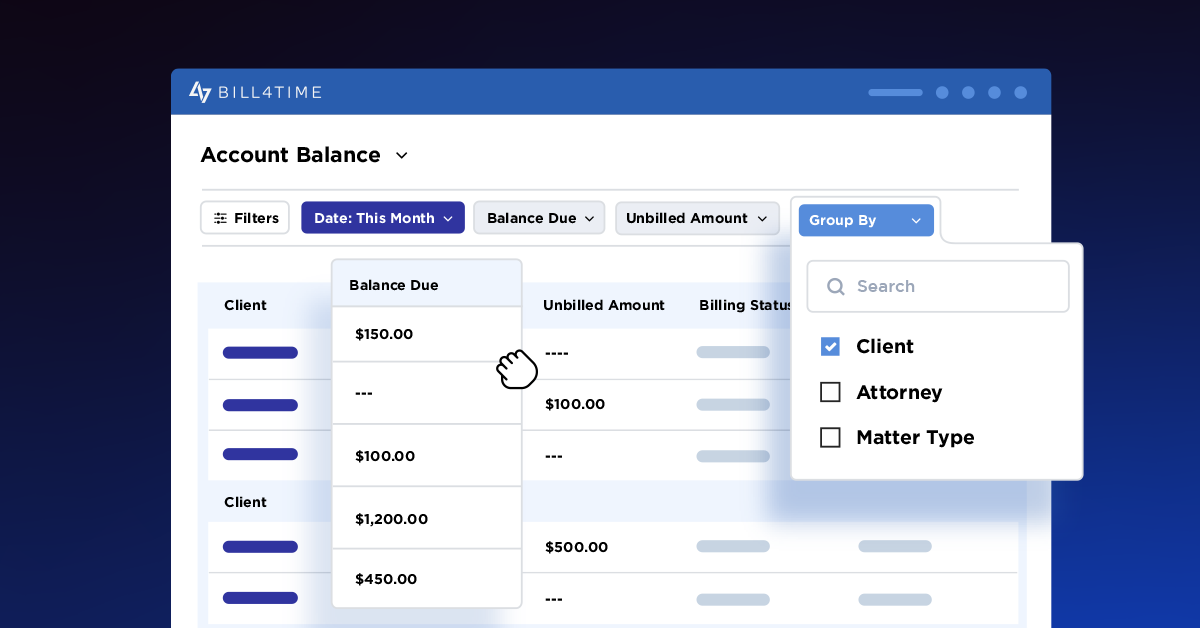

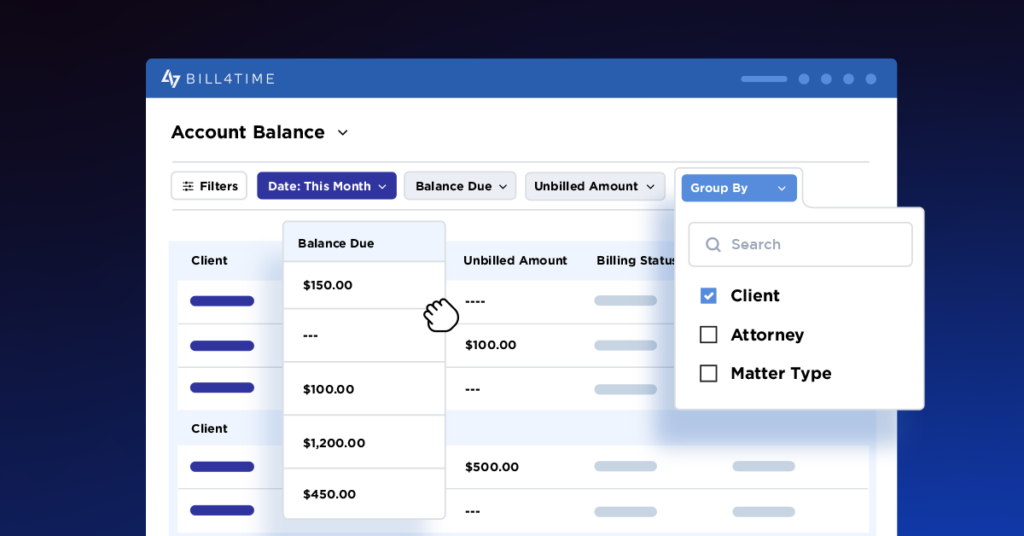

Take Greater Control of Your Firm’s Data with Bill4Time’s New Advanced Customiza

Most law firms don’t have a data problem; they have a visibility problem. Time, expenses, billing, and client activ...

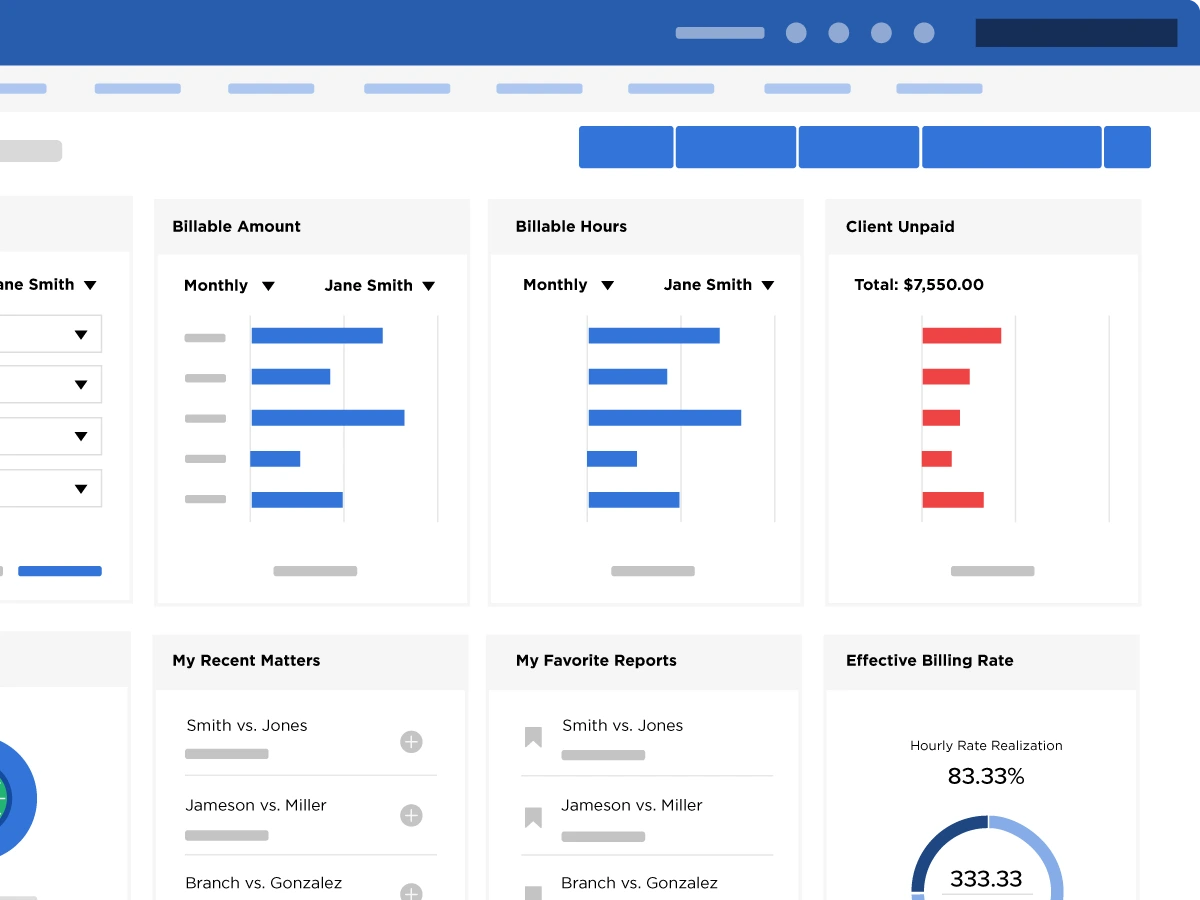

How Many Hours Should an Attorney Bill a Year? Setting Realistic Expectations Fo

How many hours should an attorney bill annually? Realistically, billing expectations shift depending on the firm, p...

The Attorney Billing Cheat Sheet: Nailing Your Billing Narrative

Billing isn’t just about sending invoices—it’s about communicating value. The way you track, describe, and present ...